Hefeweizen

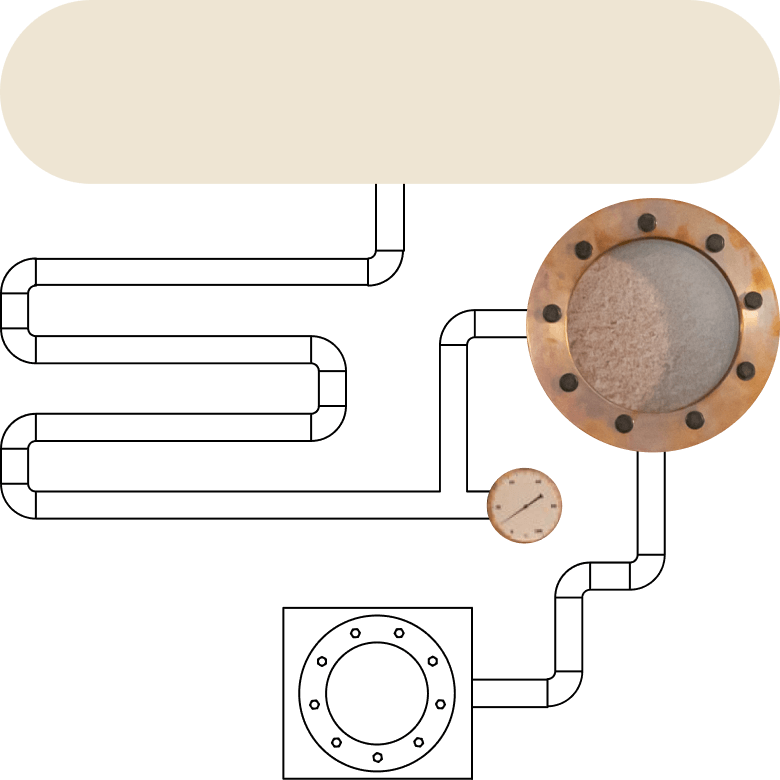

${i18n('varv')}

Hefeweizen varies from pale to amber in colour.

What is Hefeweizen?

Hefe in German means "yeast" and weizen means "wheat" Hefeweizen or hefeweißbier is an unfiltered German wheat beer served with yeast. Alongside hefeweizen, terms such as weizenbier, weißbier, or simply weizen are used.

By German law, at least 50% of the malt used must be wheat malt. Hefeweizen is known for its low bitterness and high level of carbonation. Top-fermenting yeast imparts banana, clove, and even a slight bubble-gum-like character to the beer.

An important flavour nuance for hefeweizen is the yeast sediment that settles at the bottom of the bottle, which should not be left lying there. Once most of the beer is poured from the bottle, it should be gently swirled in hand to capture the flavourful yeast settled at the bottom. Therefore, it’s always worth drinking hefeweizen from a glass.

Origin Story

The first evidence of wheat beer brewing in Europe dates to 800 BC in Bavaria. It is known that by the 14th century, wheat beer had become a very popular drink in Bavaria.

A significant milestone in beer history was the enactment of the "Beer Purity Law" or "Reinheitsgebot" in Bavaria in 1516. This law stipulated that only barley, hops, and water could be used for brewing beer. The main purpose of the law was to prohibit the use of wheat and rye in beer production to avoid competition between brewers and bakers and ensure the availability of affordable bread.

In 1520, a nobleman named Baron Hans Sigismund von Degenberg managed to acquire a special privilege to brew wheat beer, making him the only wheat beer brewer and distributor in all of Bavaria.

After his death, the exclusive right passed to Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria, who founded the royal brewery Weißes Hofbräuhaus (literally "White Court Brewery") to brew wheat beer. The production of wheat beer as an aristocratic privilege did not remain confined within the walls of Munich. Electors across Bavaria established their own wheat beer breweries and wheat beer became the drink of the nobility.

Although brewing was prohibited by German law from St. George’s Day to St. Michael’s Day, this restriction did not apply to wheat beer, thus boosting its popularity.

With the advent of new beer styles, demand for wheat beer among the upper class decreased in the 18th century and its production was no longer profitable. Between 1800 and 1812, most electorates closed or sold their breweries. By 1812, only two wheat beer breweries were left in Munich.

This could have meant the end of weissbier, but a brewer of common origin, Georg Schneider, managed to negotiate with the king for the right to continue brewing wheat beer. Thus, after centuries of exclusivity, wheat beer became accessible to the common people once again.

This coincided with the rise in popularity of pale lager beers, which hindered wheat beer from reclaiming its previous popularity. Interest in wheat beer began to grow again in the second half of the 20th century and has continued to trend upward. Today, German-style wheat beer is brewed worldwide, but Bavaria remains the largest producer and exporter.

${i18n('vol')}

4.3-5.6%